When talking about scaling an application, people are usually referring to performance: how to design the software so that limited hardware can support millions of users? But it is also important to be able to scale the feature set of an application. If users say they want a new button, you don’t want to have to make extensive refactorings of your core model classes as is all too often the case in industry. The key to both of these related demands is decoupling.

While writing the Libanius quiz application, I found typeclasses to be very useful in decoupling behaviour from the model classes. Typeclasses (formally spelt “type classes”) originated in Haskell, but can be used in Scala too, being a language that supports FP well. I’ll describe one use of typeclasses in Libanius, an example that should be less “theoretical” and more extended than the ones that are usually given.

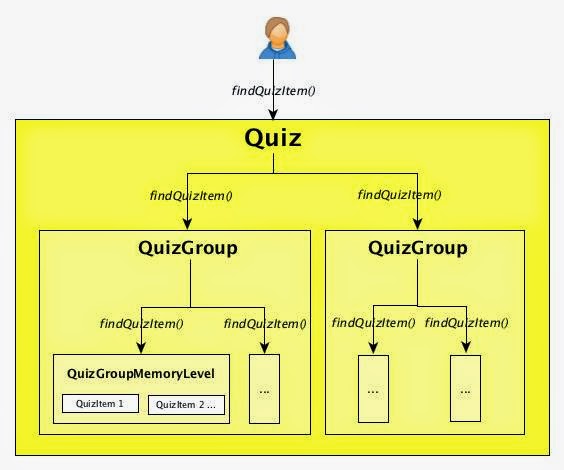

To start with, the core model in Libanius is a simple containment hierarchy as shown in the diagram. The Quiz data structure contains all the information necessary to provide a stream of quiz items to a single user. It is split by topic into QuizGroups, which, for performance reasons, are further partitioned into “memory levels” according to how well the user has learned the items. The flow of a typical request then is Quiz.findQuizItem() followed by QuizGroup.findQuizItem() calls, followed by QuizGroupMemoryLevel.findQuizItem() calls.

In practice the findQuizItem() signatures and functionality were similar but not identical. Rather than have them scattered throughout the model classes, it was desirable to put them together in a single place where the similarites could be observed and moulded, avoiding any unnecessary repetition. The same was true of other operations in the model classes. Pulling them out would also solve the problem of too much bloat in the model.

Furthermore, although the Quiz data structures are optimized for finding quiz items, I wanted to be able to extend the same action to other entities. A wide range of scenarios can be imagined:

- A Twitter feed of quotes might be seen as a mapping from speakers to quotations, which could be turned into a Who-Said-What quiz.

- A set of web pages with recipes could be read as a “What ingredient goes with what dish?” quiz.

- In a chat forum context, a person might be thinking of quiz questions and feeding them through.

- A clever algorithm might not simply be “finding” quiz items in a store, but dynamically generating them based on previous answers.

- The Quiz might not be a Scala data structure, but a database. This could be a NoSQL in-memory database like Redis or leveldb. It could also be a traditional RDBMS like Postgres accessed via Slick.

What links all these cases together is that a findQuizItem() function is necessary but with a new implementation. So the immediate priority is to decouple the findQuizItem() action from the simple Quiz data structure. Notice that this action might be applied to structures that didn’t even know they were supposed to be quizzes. We don’t want to have to retroactively modify classes like TwitterFeed and ChatParticipant to make them “quiz aware”.

If you know a lot of Java, some design patterns might occur to you here, like Adapter, Composite, or Visitor. In the Visitor pattern, in particular, you can separate out arbitary operations from the data structures and form a parallel hierarchy to run those operations. But the original data structures still have to have an accept() method defined. In Scala a more convenient alternative, graced with all the polymorphism you could ever need, is the typeclass construct. Typeclasses excel at separating out orthogonal concerns.

Firstly a trait is defined for the typeclass with the behaviour we wish to separate out. Let’s begin by calling the main function produceQuizItem() rather than findQuizItem(), to abstract it more from the implementation:

trait QuizItemSource[A] {

def produceQuizItem(component: A): Option[QuizItem]}

}

The component could be a Quiz, a QuizGroup, a QuizGroupMemoryLevel or anything else. Instead of calling produceQuizItem() on the component, the component is passed as a parameter to the operation.

Next, define some sample implementations (aka typeclass instances) for the entities (aka model components) that we already have:

object modelComponentsAsQuizItemSources {

implicit object quizAsSource extends QuizItemSource[Quiz] {

def produceQuizItem(quiz: Quiz): Option[QuizItem]} =

… // implementation calls methods on quiz

}

implicit object quizGroupAsSource extends QuizItemSource[QuizGroup] {

def produceQuizItem(quizGroup: QuizGroup): Option[QuizItem]} =

… // implementation calls methods on quizGroup

}

implicit object quizGroupMemoryLevelAsSource extends QuizItemSource[QuizGroupMemoryLevel] {

def produceQuizItem(quizGroupMemoryLevel: QuizGroupMemoryLevel): Option[QuizItem]} =

… // implementation calls methods on quizGroupMemoryLevel

}

}

These sample implementations can be accessed in client code once it is imported in this way:

import modelComponentsAsQuizItemSources._

If you’re coming from other languages, it’s the use of the implicit that is at first difficult to grasp, but this is really the Scala feature that makes typeclasses convenient to use, where they are not in, say, Java. Let me explain what is happening here:

Suppose in client code, the modelComponentsAsQuizItemSources has been imported as above. Now the quizGroupAsSource is implicitly in scope, among other implementations. If there is now a call to QuizItemSource.produceQuizItem(quizGroup), the compiler, seeing that quizGroup is of type QuizGroup will match qis to an implicit of type QuizItemSource[QuizGroup]: this is quizGroupAsSource, the correct implementation.

The great thing is that the correct QuizItemSource implementation will always be selected based on the type of entity passed to produceQuizItem, and also the context of the client, specifically the imports it has chosen. Also, we have achieved our original goal that whenever we realize we want to turn an entity into a quiz (TwitterFeed, ChatParticipant, etc.) we don’t have to modify that class: instead, we add an instance of the typeclass to modelComponentsAsQuizItemSources and import it.

This approach is a break with OO, moving the emphasis from objects to actions. Instead of adding actions (operations) to objects, we are adding objects to an action generalization (typeclass). We can make that action as powerful as we like by continuing to add objects to it. Again, unlike in OO, those objects do not need to be custom-built to be aware of our action.

That is the main work done. There are two more advanced points to cover.

Firstly, it is possible to add some “syntactical sugar” to the definition of produceQuizItem() above. In this code

def produceQuizItem[A](component: A)(implicit qis: QuizItemSource[A]): Option[QuizItem] =

qis.produceQuizItem(component)

… the qis variable may be viewed as clutter. We can push it into the background using context bound syntax:

def produceQuizItem(A : QuizItemSource](component: A): QuizItem =

implicitly[QuizItemSource].produceQuizItem(component)

What happens is that the context bound A : QuizItemSource establishes an implicit parameter, which is then pulled out by implicitly. This syntax is a bit shorter, and looks shorter still if you do not need to call implicitly but are simply passing the implicit parameter down to another function.

Secondly, it is possible to have a typeclass with multiple type parameters. Context bound syntax is not convenient for this case, so, first, let’s go back to the original syntax:

def produceQuizItem[A](component: A)(implicit qis: QuizItemSource[A]): Option[QuizItem] =

qis.produceQuizItem(component)

Suppose a Quiz were passed in, the quizAsSource instance will be selected. You will remember this looked like this:

implicit object quizAsSource extends QuizItemSource[Quiz] {

def produceQuizItem(quiz: Quiz): Option[QuizItem]} =

… // implementation calls methods on quiz

}

However, I simplified a bit here. The original implementation did not in fact return simple quiz items in the case of a Quiz. Whenever the Quiz retrieved a quiz item from a QuizGroup, it would add some information. Specifically it would generate some “wrong choices” for the question and return that to the user to allow a multiple-choice presentation of the quiz item. So the QuizItem would be wrapped in a QuizItemViewWithChoices object. The signature had to be:

def produceQuizItem(quiz: Quiz): Option[QuizItemViewWithChoices]} = …

Now the problem is this does not conform to the typeclass definition. So let’s massage the typeclass definition a bit by turning the return type into a new parameter, C:

trait QuizItemSource[A, C] {

def produceQuizItem(component: A): Option[C]

}

Then the typeclass instance for Quiz will look as desired:

implicit object quizAsSource extends QuizItemSource[Quiz, QuizItemViewWithChoices] {

def produceQuizItem(quiz: Quiz): Option[QuizItemViewWithChoices]} =

… // implementation calls methods on quiz

}

The intermediate function for accessing the typeclass becomes a bit more complex. Recall this was previously:

def produceQuizItem[A](component: A)

(implicit qis: QuizItemSource[A]): Option[QuizItem] =

qis.produceQuizItem(component)

The second type parameter for the return type is added as C:

def produceQuizItem[A, C](component: A)

(implicit qis: QuizItemSourceBase[A, C], c: C => QuizItem): Option[C] =

qis.produceQuizItem(component)

C is constrained so that the return value must be compatible with QuizItem. To make QuizItemViewWithChoices compatible with QuizItem, it is not necessary to make it a subclass with lots of boilerplate as in Java. Instead an implicit conversion is defined next to the QuizItemViewWithChoices class like this:

object QuizItemViewWithChoices {

// Allow QuizItemViewWithChoices to stand in for QuizItem whenever necessary

implicit def qiView2qi(quizItemView: QuizItemViewWithChoices): QuizItem =

quizItemView.quizItem

}

Now it all works!

That ends the description of the QuizItemSource typeclass. For more examples, see the other typeclasses in the Libanius source code such as CustomFormat and ConstructWrongChoices, which cover other concerns orthogonal to the model, or view this excellent video tutorial by Dan Rosen.